Madala

In my early twenties, I ran a store in the farm and those nine years turned out in time to have been a very good education.

At the time I thought that I was wasting away. Wasting the best years of my life. While my peers used that time to become professionals I lazed around scratching a living in Umlaas Road.

Newly married, we made a home in the middle of nowhere. My Zulu improved a lot and I never missed the opportunity to engage in conversation and banter with my customers. That connection was valuable to me. I craved the approval of others and life was good.

Pretending at being grown up.

I laughed a lot and played loud music in the store. It was hard because money was tight, but we made a decent life.

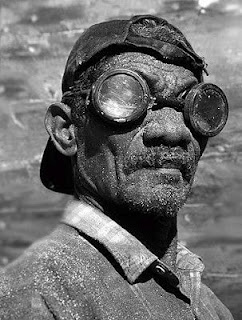

There was an old man who worked odd jobs whom we called Madalla. Which means "old man". To this day I don't know what his actual name was. We inherited him with the place and that's what he was called. Madalla.

He was old and banged up, but I question that now. I now know that when a young man perceives somebody as old, they really didn't know anything. I often realised that the people I called really old were actually in their forties.

So he was "old", hard of hearing and could barely see anything. My dad insisted that he be fitted with spectacles and he ended up with comically huge lenses and apparently could see well enough to work.

I don't remember ever speaking to him or seeing him talk to anyone. We treated him like a pack mule. He was strong and not very bright. I think we saw him this way as his poor hearing prevented him from communicating effectively. We will never know if he was dim or just deaf.

He came into the store three times a day and I gave him his meals. For breakfast he had maas and bread, lunch was a liter of Mahew and supper a tin fish bunny. Looking back now he really did have a dog's life.

Most of my customers were poor labourers and they carried the air of hard labour with them. They were sometimes a little ripe, but mostly they were as clean as they could afford to be.

Madala was different. He didn't care for personal hygiene and that was another reason why nobody got too close to him.

Or so I thought.

This old, half-deaf, half-blind, half-witted filthy man had a secret.

Once in a while, women were seen sneaking out of the junkyard where he lived. Different women, who looked pretty normal were having secret meetings with Madala.

We couldn't figure out why anyone would want to be near the filthy old man and simply assumed he must be very well endowed.

Perhaps his blindness and deafness were compensated by a magic flute?

It was beyond comprehension what the women saw in that filthy beast.

Looking back now I see things very differently. How I wish I had not squandered the opportunity that I was given.

I didn't have much, but I had much more than those who were in my care.

We could have helped with his hearing, spoken to him and found out more about his life. We could have, not treated him like a pack mule, and given him the dignity of being a man.

Maybe I would have found a man struggling with his own demons.

M Parak

MAR 2021

At the time I thought that I was wasting away. Wasting the best years of my life. While my peers used that time to become professionals I lazed around scratching a living in Umlaas Road.

Newly married, we made a home in the middle of nowhere. My Zulu improved a lot and I never missed the opportunity to engage in conversation and banter with my customers. That connection was valuable to me. I craved the approval of others and life was good.

Pretending at being grown up.

I laughed a lot and played loud music in the store. It was hard because money was tight, but we made a decent life.

There was an old man who worked odd jobs whom we called Madalla. Which means "old man". To this day I don't know what his actual name was. We inherited him with the place and that's what he was called. Madalla.

He was old and banged up, but I question that now. I now know that when a young man perceives somebody as old, they really didn't know anything. I often realised that the people I called really old were actually in their forties.

So he was "old", hard of hearing and could barely see anything. My dad insisted that he be fitted with spectacles and he ended up with comically huge lenses and apparently could see well enough to work.

I don't remember ever speaking to him or seeing him talk to anyone. We treated him like a pack mule. He was strong and not very bright. I think we saw him this way as his poor hearing prevented him from communicating effectively. We will never know if he was dim or just deaf.

He came into the store three times a day and I gave him his meals. For breakfast he had maas and bread, lunch was a liter of Mahew and supper a tin fish bunny. Looking back now he really did have a dog's life.

Most of my customers were poor labourers and they carried the air of hard labour with them. They were sometimes a little ripe, but mostly they were as clean as they could afford to be.

Madala was different. He didn't care for personal hygiene and that was another reason why nobody got too close to him.

Or so I thought.

This old, half-deaf, half-blind, half-witted filthy man had a secret.

Once in a while, women were seen sneaking out of the junkyard where he lived. Different women, who looked pretty normal were having secret meetings with Madala.

We couldn't figure out why anyone would want to be near the filthy old man and simply assumed he must be very well endowed.

Perhaps his blindness and deafness were compensated by a magic flute?

It was beyond comprehension what the women saw in that filthy beast.

On the farm, we used to dispose of garbage by throwing it into a pit in the ground. When it filled up we burned it and this compacted it. After a few years when it absolutely couldn't hold any more, we covered it and dug a new one. One morning I told Madala that we needed a new pit. I knew this as I would often go to the pit and enjoy target practice on the rats that lived in the hole. A few weeks later when I asked the staff what he was doing they said he was still digging the new pit. He came for his meals every day and I hadn't thought to ask what he was doing. I was surprised that he was still digging after all that time, so I decided to go and take a look for myself. What I found was incredible. Madala could barely be seen from the surface. Every morning he went into the pit with a ladder and when he came up for lunch he brought out the displaced sand in buckets. Apparently, if I hadn't told him to stop, he would have just kept going, stopping only when he surfaced in China.

Looking back now I see things very differently. How I wish I had not squandered the opportunity that I was given.

I didn't have much, but I had much more than those who were in my care.

We could have helped with his hearing, spoken to him and found out more about his life. We could have, not treated him like a pack mule, and given him the dignity of being a man.

Maybe I would have found a man struggling with his own demons.

M Parak

MAR 2021

Comments